The Industrial Revolution was a period of rapid social and technological change that shaped the world we live in today. It was a period of great innovation, and many of the tools we see today were inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

The following 34 inventions are a hand-picked selection of some of the most important inventions of the period and some of the lesser-known ones. If it tickles your fancy, we also have a video embedded below.

- Why Did the Industrial Revolution Start in Britain?

- 35 inventions that changed the world

- 40 greatest engineers who made enormous impacts on the world

The inventions include changes in the textile industry, the iron industry, and consumer goods made during the later part of the Industrial Revolution. They are in no particular order.

1. The flying shuttle made weaving made easy

Betty Longbottom/Wikimedia Commons

This great example was widely used throughout Lancashire after 1760 and was one of the critical developments of the period. It was patented in 1733 by John Kay, and it allowed one weaver to weave fabrics of any width more quickly than two could before.

Before this invention, a weaver was required on each side of a broad-cloth loom. Now, one weaver alone could do the job of two. Several subsequent improvements were made to it over the years, with an important one in 1747.

Its impact was incredibly significant, effectively allowing the production of textiles to increase beyond the capacity of the rest of the industry. It arguably prompted further industrialization throughout the textile and other industries to keep up.

2. The spinning jenny increased wool mills' productivity

Markus Schwei?/Wikimedia Commons

The spinning jenny was another example of the great invention of the Industrial Revolution. It was developed by James Hargreaves, who patented his idea in 1764.

The spinning jenny was groundbreaking during its time and would help change the textile industry - and the way many people worked - forever. The machine allowed a single operator to spin thread onto eight spindles at once by turning a single wheel. Later improvements increased this to eighty.

This vastly increased mill productivity and, along with the flying shuttle, helped force further industrialization of the textile industry in the United Kingdom.

It allowed for a massive reduction in the work needed to produce a piece of cloth, greatly increased the demand for cotton, wool, and other materials that could be woven into clothing, and lowered the price of cloth.

Hargreaves and jenny have also been credited as the main driver for developing a modern factory system. By his death in 1778, there were around 20,000 spinning Jennys across the UK.

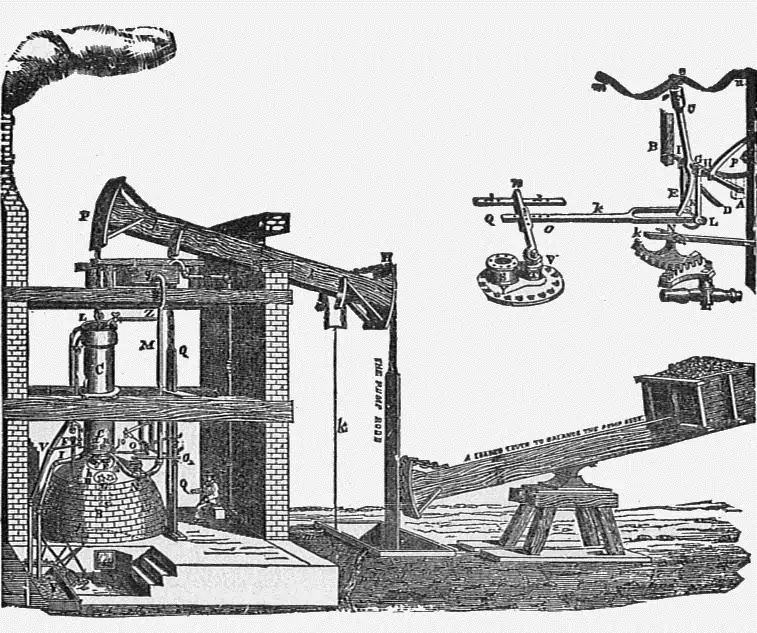

3. The Watt steam engine changed the world

Andy Dingley/Wikimedia Commons

When James Watt created a much more efficient steam engine in 1769, his invention changed the world. His innovation blew the older, less efficient models out of the water, like the Newcomen engine.

James' innovation of adding a separate condenser significantly improved steam engine efficiency, especially latent heat losses. His new engine would be very popular and installed in mines and factories worldwide.

It was, hands down, one of the greatest inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

His version also integrated a crankshaft and gears, and it became the prototype for all modern steam engines. It would eventually lead to incredible improvements in almost all industries, including the textile and transportation industries, across the world.

Steam engines would also lead to the development of locomotives and massive leaps forward in ship propulsion.

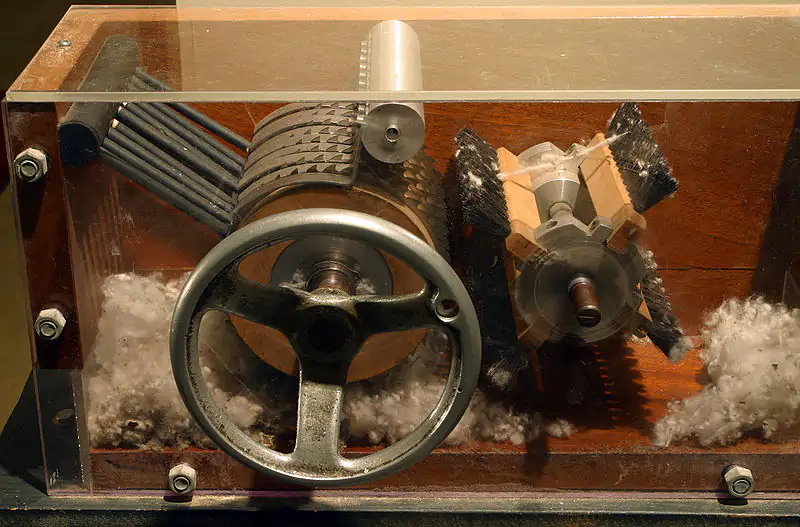

4. The cotton gin: the engine that made cotton production boom

Brighterorange/Wikimedia Commons

Eli Whitney is another name synonymous with inventions of the Industrial Revolution. He invented the cotton engine, or gin for short, in 1794.

Before its introduction into the textile industry, cotton seeds needed to be removed from fibers by hand; this process was laborious and time-consuming. This machine vastly improved the profitability of cotton for farmers.

The Cotton Gin enabled many more farmers to consider growing cotton as their main crop. This was especially significant for farmers and slave plantation owners in the Americas.

With the seeds and fibers separated more efficiently, it became much cheaper for farmers to grow cotton for goods like linen. They could also simultaneously separate seeds for crop growth or cottonseed oil production.

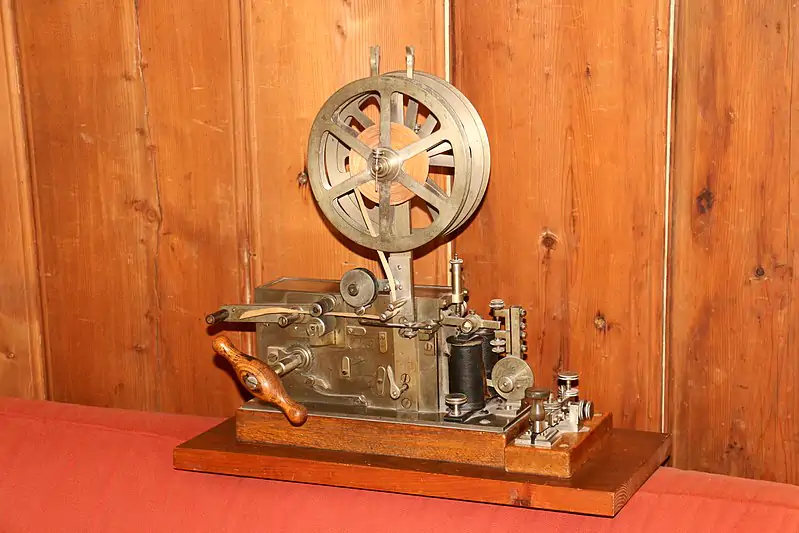

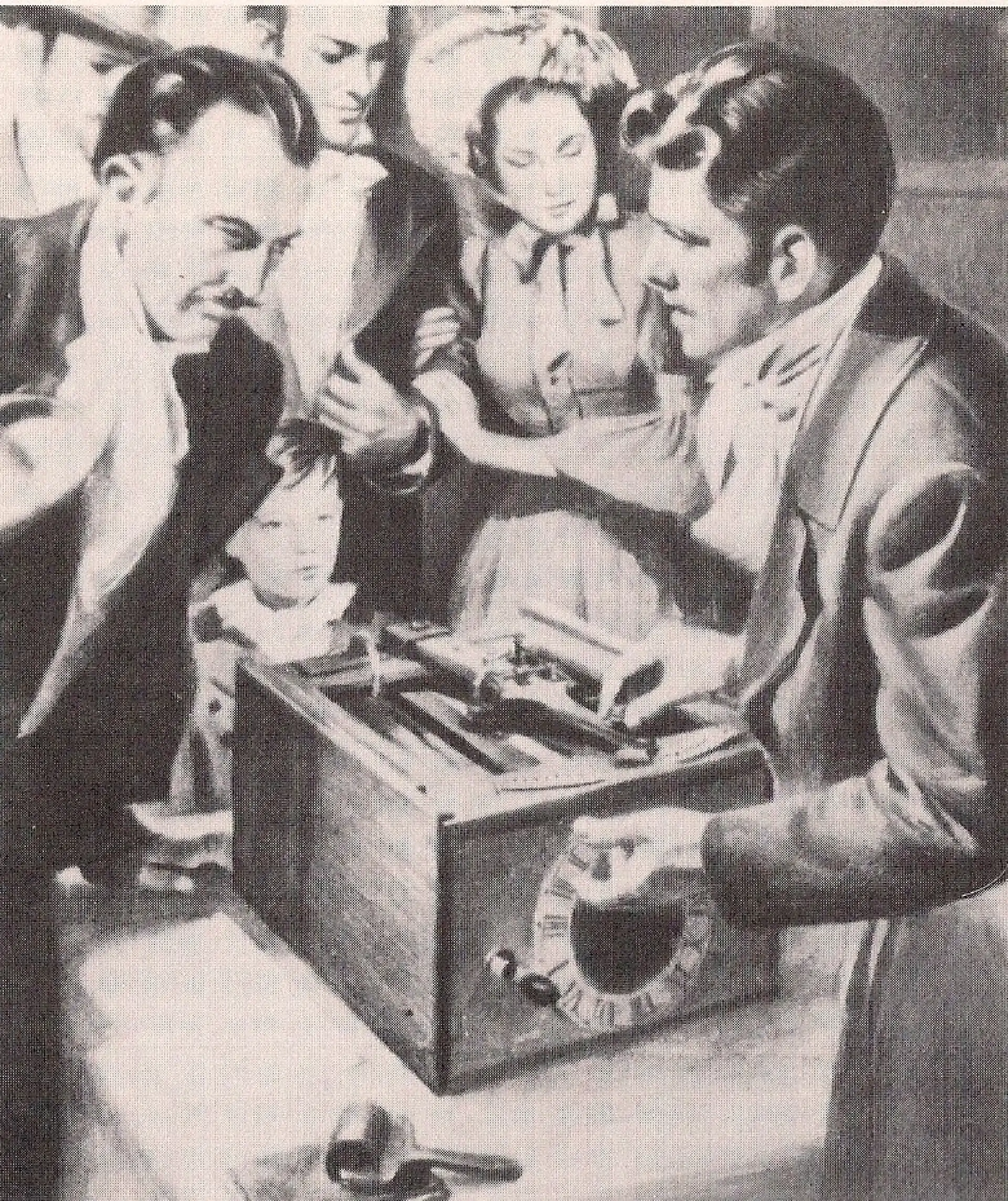

5. Telegraph communications were a pillar of the Industrial Revolution

Hp.Baumeler/Wikimedia Commons

The telegraph was another of the greatest inventions of the Industrial Revolution. The first two practical electric telegraphs appeared at almost the same time. In 1837, two British inventors obtained a patent for a telegraph system that employed six wires and actuated five needle pointers attached to five galvanoscopes at the receiver. If currents were sent through the proper wires, the needles could be made to point to specific letters and numbers on their mounting plate.

That same year, American inventor Samuel Morse was granted a patent for the "American Recording Electro-Magnetic Telegraph", which used the now familiar system of dots and dashes.

This technology changed communication forever. It made very rapid communication possible across the country and eventually across the globe. This enabled people to stay in contact, allowed safer traffic control on railways, and become more aware of broader geopolitical events. In only a few years, the electrical telegraph became the de facto means of communication for businesses and private citizens long distance.

6. Portland cement and the reinvention of concrete was another major milestone

Nichtbesserwisser/Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Aspdin was a bricklayer turned builder who, in 1824, devised and patented a chemical process for making Portland Cement. This one invention from the Industrial Revolution has been one of the most important for the construction industry.

His process involved sintering a mixture of clay and limestone to around 2,552 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius). This was then ground into a fine powder. When mixed with water, the anhydrous calcium silicates in the portland cement react chemically and harden into a very strong substance. Portland cement is mixed with sand and gravel to make concrete.

Years later, civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel would use Portland Cement to help construct the Thames Tunnel. It was also used on a large scale in constructing the London sewage system and many other construction projects worldwide to this day.

It was also one of the greatest inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

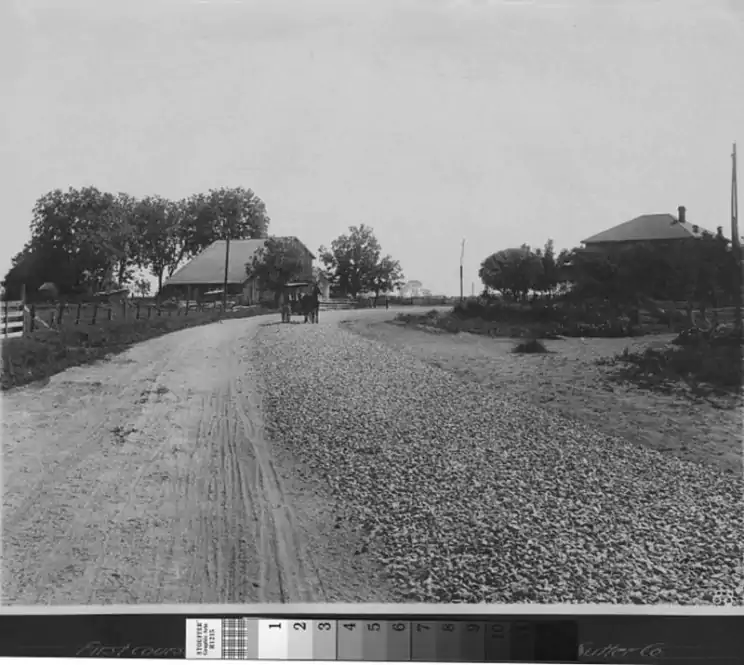

7. John McAdam's roads were a vast improvement

Sutter County Library/Wikimedia Commons

Before the Industrial Revolution, the quality of Britain's roads was less than great. Many British roads were poorly maintained and of poor quality. During the 1700s, turnpike trusts were set up to charge tolls and use the money to improve maintenance and the quality of the country's transport system.

By 1750 almost every main road in England and Wales was the responsibility of a turnpike trust.

John McAdam would eventually develop a new road-building technique that would revolutionize road construction forever. His 'macadamized' roads used crushed stone in shallow, convex layers, a binding layer of stone dust, and a cement or bituminous binder. This method greatly simplified the process of road building and soon became standard.

8. The Bessemer process was vital for modern steel

Calle Eklund/V-wolf/Wikimedia Commons

The Bessemer process was the world's first inexpensive process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron. This would also prove to be one of the greatest inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

It is noted for removing impurities from the iron via oxidation as air is blown through the molten metal. Oxidation also helps raise the temperature of the iron mass to keep it molten for longer. The process is named after its inventor Henry Bessemer who patented the technique in 1856.

The ability to mass-produce high-quality steel and iron allowed a literal boom in using them in many other aspects of the revolution. Iron and steel suddenly became essential materials used to make almost everything from appliances to tools, machines, ships, buildings, and infrastructure.

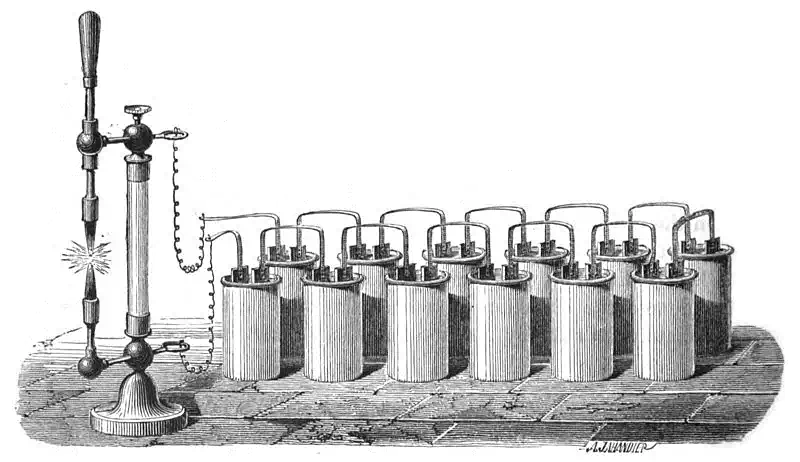

9. The first modern battery was a game changer

GuidoB/Wikimedia Commons

Although there is evidence of early batteries from as far back as the Parthian Empire around 2,000 years ago, the first true electric battery was invented in 1800. This world-first was the brainchild of one Alessandro Volta with the development of his voltaic pile.

In 1802, William Cruickshank designed the first electric battery capable of being mass-produced.

The first rechargeable battery marketed for commercial use was invented in 1859 by the French physician Gaston Plante. Later advancements would lead to the nickel-cadmium battery being developed in 1898 by Waldemar Jungner.

Volta's initial invention sparked a significant amount of scientific excitement worldwide, leading to the eventual development of the field of electrochemistry.

10. The locomotive ushered in a revolution of its own

Urmelbeauftragter/Wikimedia Commons

The invention of the steam engine would eventually lead to a revolution in transportation around the globe. Locomotives allowed large-scale movement of resources and people rapidly over long distances.

Previously, transportation relied on animal-powered wagons and carts or ships for longer distances.

After the pioneering work of Richard Trevithick in 1804 and of George Stephenson and his "Rocket," railway networks would begin to spring up all over the United Kingdom and eventually the world.

The first public railway opened in 1825 between Stockton and Darlington in England, UK. This would be the first of many railways and locomotives to revolutionize how business and private citizens transport their goods and themselves.

11. The first factory opened by Lombe

ClemRutter/Wikimedia Commons

John Lombe opened one of, if not the, first documented factory in Derby around 1721. Lombe's factory used water power to help the factory mass produce silk products.

The factory was built on an island on the River Derwent in the English county of Derby. The idea for the factory came to Lombe after he had toured Italy looking at silk-throwing machines.

On his return to the UK, he employed architect George Sorocold to design and build his new "Factory." Once completed, the mill, at its height, employed around 300 people.

On its completion, it was the first successful silk-throwing mill in England and, it is believed by many to be the first fully mechanized factory in the world. Lombe was granted a 14-year patent for his throwing machines, only to die mysteriously in 1722. One rumor attributed his death to the King of Sardinia, who reacted badly to the commercialization of silk production in the UK.

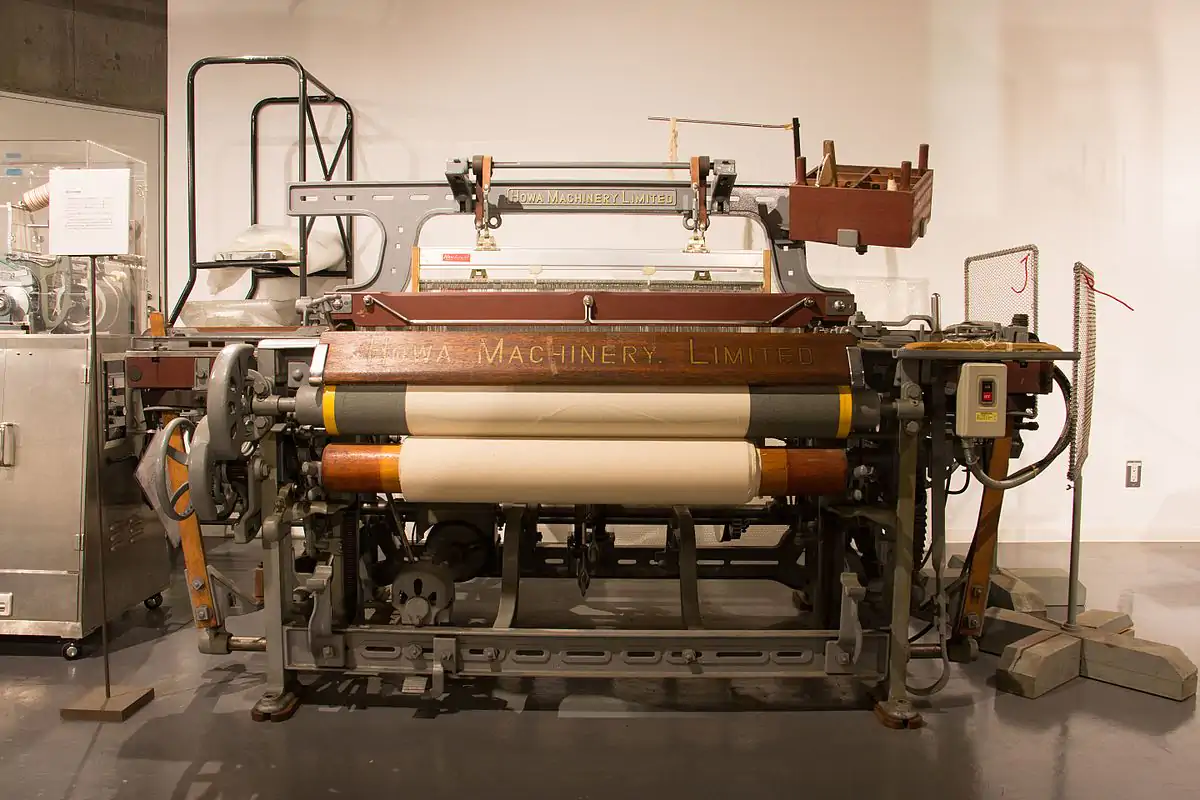

12. The power loom proved to be a huge success

Fumihiro Kato/Wikimedia Commons

The invention of the power looms effectively increased the output of a worker by a factor of 40. It was one of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution.

It was introduced by Edmund Cartwright, who built the very first working machine in 1785. Over the next 60 years or so, the power loom was refined by a number of people until it was made entirely automated in 1848 by Kenworthy & Bullough.

By 1850, around 260,000 power looms were installed in factories throughout the United Kingdom.

Cartwright's power loom was first licensed by Grimshaw of Manchester, who built a small steam-powered weaving factory in 1790. Sadly this soon burnt down. Initially, his looms were not a commercial success as they needed to be stopped to dress the warp.

This was soon addressed over the next few decades as he modified the design into a more reliable automated machine.

13. Arkwright's water frame was another huge technological step forward

ClemRutter/Wikimedia Commons

Richard Arkwright was a barber and wig maker who devised a machine to spin cotton fibers into yarn or thread quickly and easily. In 1760 he and John Kay managed to produce a working machine. This prototype could spin four strands of cotton at the same time.

He would later patent his design in 1769. Further refinement of his design would allow the machine to spin hundreds of strands simultaneously.

The spinning machine would go on to be installed in mills around Derbyshire and Lancashire, where they were powered by waterwheels hence they were called water frames. Arkwright's machines alleviated the need for highly skilled operators, adding significant cost savings to mills that installed them.

14. The spinning mule: the yarn game-changer

Black Stripe/Wikimedia Commons

The spinning mule combines features of two earlier Industrial Revolution inventions: the spinning jenny and the water frame mentioned above. The spinning mule produced a strong, delicate, soft yarn that could be used in many textiles.

It was, however, best suited for the production of muslins. Samuel Crompton devised the Mule in 1775; he was too poor to patent his invention and sold it to a Bolton manufacturer. It was soon being produced and adapted by others. The first Mules were hand-operated, but by the 1790s, larger versions were driven by steam engines. These larger machines had as many as 400 spindles.

By 1812, between 4 and 5 million mules were in use, but Crompton received no royalties for the invention. The principles of his design continued to be used until the early 1980s.

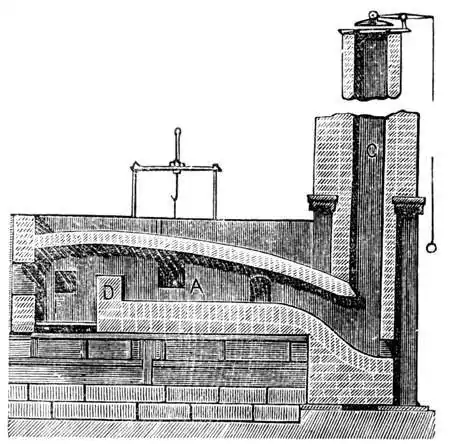

15. Henry Cort's puddling process was groundbreaking

Helix84/Wikimedia Commons

In 1784, Henry Cort developed a method of converting pig iron into wrought iron by heating it and frequently stirring it in the presence of oxidizing substances. It was, at the time, the first method that allowed wrought iron to be produced on a large scale.

Cort had saved a large amount of capital during his 10-year service in the Royal Navy. With this money had bought an ironworks near Portsmouth in 1775.

By 1783 he obtained a patent for grooved rollers that would allow him to produce iron bars more quickly than the old method of hammering.

His puddling process would take the iron industry by storm; British iron production quadrupled over the following 20 years!

16. Gaslighting; lighting the streets of the modern world

Chris Allen/Geograph.org.uk

Commercial gas lighting was first developed and introduced in 1792 by William Murdoch. His first gas lights used coal gas and were installed as the lighting in his house in Redruth, Cornwall.

Over a decade later, German inventor Freidrich Winzer became the first to patent coal gas for lighting in 1804. A thermo-lamp was also developed in 1799 using gas distilled from wood, and David Melville received the first patent in the U.S. for gas lighting in 1810.

After its development, gas lighting became the method of street lighting across the United States and Europe. These would eventually be replaced with low-pressure sodium or high-pressure mercury lighting in the 1930s.

17. The first arc lamp laid the foundations for some modern forms of lighting

Chetvorno/Wikimedia Commons

Sir Humphrey Davy was able to build the world's first arc lamp in 1807. His device used a battery of 2,000 cells to create a 3 ??/??-inch (100mm) arc between two charcoal sticks.

As impressive as his initial success was, it was not a practical piece of equipment until the development of electrical generators in the 1870s. Arc lamps are still used in applications like searchlights, large film projectors, and floodlights.

The term is usually limited to lamps with an air gap between consumable carbon electrodes. but fluorescent and other electric discharge lamps generate light from arcs in gas-filled tubes.

Today, some ultraviolet lamps are also based on the same concept.

18. The tin can was a surprising success

Chris Potter/Wikimedia Commons

The humble tin can was patented by a British merchant Peter Durand in 1810. It would have an incalculable impact on food preservation and transportation up to the present day.

John Hall and Bryan Dorkin opened the very first commercial canning factory in England in 1813. In 1846, Henry Evans invented a machine that could manufacture tin cans at a rate of sixty per hour.

This was a significant improvement over the previous rate of only six per hour.

The first tin cans had thick walls and needed to be opened with a hammer and chisel. Over time they became thinner, enabling the invention of a dedicated can opener in 1855 in England and 1858 in the United States.

It took the American Civil War to inspire the creation of tin cans with a key opener, as can still be found on sardine cans.

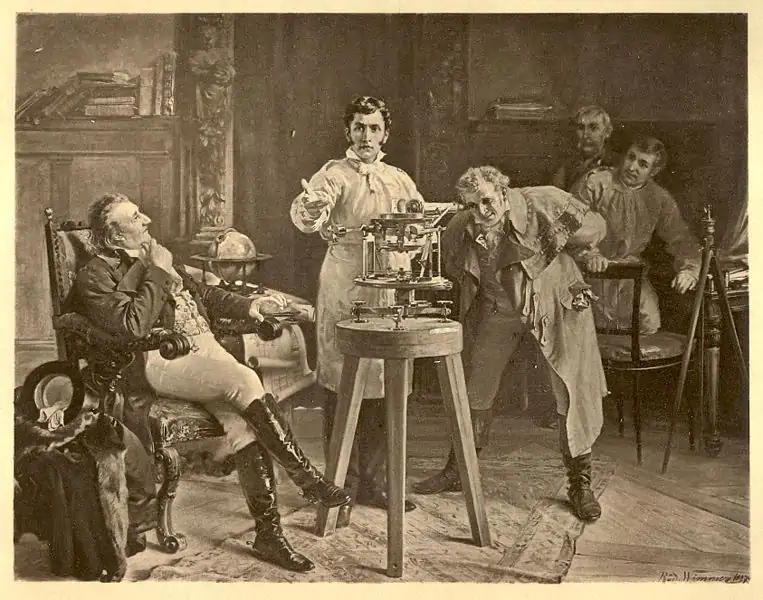

19. The spectrometer has proved very useful over time

Richard Wimmer/Wikimedia Commons

Generally, Sir Isaac Newton is credited with the discovery of spectroscopy. However, the first spectrometer wasn't created until 1802 when William Hyde Wollaston improved on Newton's work.

Wollaston's spectrometer included a lens that focused the Sun's spectrum on a screen. He quickly noticed that the spectrum was missing sections of color. In 1815, German inventor Joseph von Fraunhofer replaced Newton's prism with a diffraction grating. Fraunhofer's experiments allowed him to quantify the dispersed wavelengths created by his diffraction grating. Today, Fraunhofer lines, and he is sometimes referred to as the father of spectroscopy.

He designed several heliometers, one of which was used in 1838 by German astronomer Friedrich Bessel to perform the first measurement of the distance between a star and Earth.

Little did von Fraunhofer know the full impact his invention would have on the scientific world. We owe the fact that we know what the Sun is made of thanks to Fraunhofer.

His discoveries earned him an appointment as a Knight of the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown by King Maximilian I, two years before his death. Like many glassmakers of the time, he died early due to heavy metal poisoning.

20. The camera obscura and the first photograph

Joanjoc~commonswiki/Wikimedia Commons

Beginning in 1814, Joseph Nicephore Niepce started a journey of discovery that would eventually lead him to become the first person ever to take a photograph. He would eventually capture an image on a sheet of bitumen-coated pewter using his new-fangled version of a camera obscura that was set up in the windows of his home in France.

The entire exposure took around 8 hours to capture the image.

Joseph constructed his first camera around 1816, which allowed him to create an image on white paper. But he was unable to fix the image.

He would continue his experimentation using different cameras and chemical combinations for the next 10 years.

In 1827 he successfully produced the first long-lasting image using a plate coated with bitumen. This was then washed in a solvent and placed over a box of iodine to produce a plate with light and dark qualities.

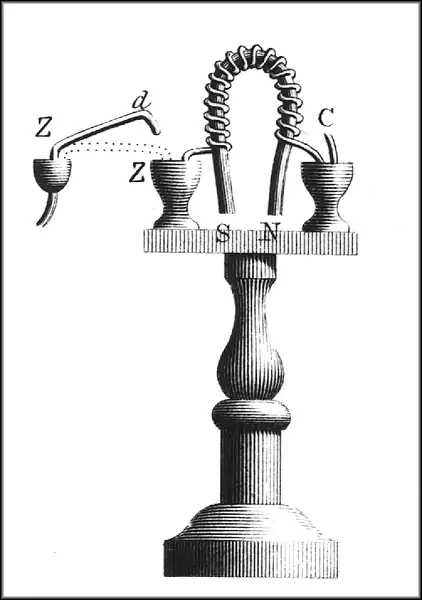

21. The first electromagnet findings

Chetvorno/Wikimedia Commons

The electromagnet was the culmination of a series of developments from Hans Christian Oersted, Andre-Marie Ampere, and Dominique Francois Jean Arago, who made critical discoveries on electromagnetism.

One man, William Sturgeon, would take the findings of these great scientists and build on them to build the world's first electromagnet in 1824.

He found that leaving some iron inside a coil of wire would vastly increase the magnetic field created. He also realized that bending the iron into a u-shape allowed the poles to come closer together, thereby concentrating the field lines.

His design was improved upon by Joseph Henry, who built, in 1832, a powerful electromagnet that was able to lift 1630 kgs.

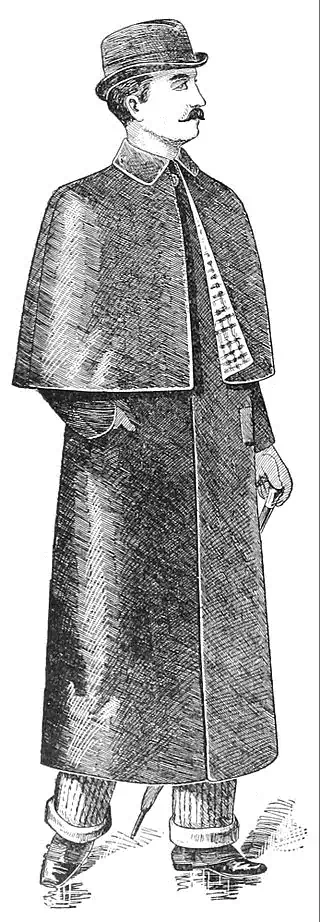

22. The Mackintosh raincoat was another great invention

Cbaile19 /Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps one of the most valuable personal inventions during the Industrial Revolution was when, in 1823, Charles Mackintosh devised the Mackintosh. Before his invention, clothing was waterproofed by using a coating of rubber.

But rubber would become sticky and tacky during hot weather and highly stiff during winter. Mackintosh, a Scottish chemist, successfully cured this problem and patented a new method of using rubber to waterproof clothing.

Initially, he created his new waterproof clothing at his family's textile factory. By 1843, Mackintosh had begun mass production of their clothes and merged with a larger clothing manufacturing company.

His method of waterproofing is known to us today as vulcanization. This process allowed the rubber to maintain its shape and not become sticky during hot weather like natural rubber.

Mackintosh's design also placed the rubber covering inside two pieces of fabric rather than covering one.

23. Modern friction matches are surprisingly old

Jef-Infojef/Wikimedia Commons

In 1826, John Walker gave the world the first modern, self-striking matches. The first self-striking match was created in 1805 by Jean Chancel in Paris. This crude match was made by coating a wooden stick with potassium chlorate, sulfur, sugar, and rubber, and then dipping it into a bottle filled with sulfuric acid. The reaction between the acid and the mixture on the stick would start a fire but also release very nasty fumes into the face of the user.

Early attempts were made to make a match that produced ignition through friction by Francois Derosne in 1816.

These were, however, crude and used the sulfur-tipped match to scrape inside a tube coated with phosphorus. This was both inconvenient and unsafe. Waker was a chemist and druggist from Stockton-on-Tees who developed a keen interest in making fire as efficiently as possible.

When, quite by accident, a prepared match ignited from friction on the hearth, he knew he had found the answer. He immediately started producing wooden splints or sticks of cardboard and coating them with sulfur.

He then added a tip with a mixture of a sulfide of antimony, chlorate of potash, and gum. Camphor was added later to mask the smell of the sulfur once ignited.

24. The typewriter also changed the world

Encyclopedia Brtiannica/Wikimedia Commons

It is widely accepted that in 1829, William Austin Burt patented the "first typewriter," which he termed a "Typographer." There were earlier machines similar in purpose, a notable example being Henry Mill's 1714 patent, but it appears to have never been capitalized upon.

The Science Museum in London describes Burt's machine as "the first writing mechanism whose invention was documented." Despite its apparent breaking of new ground, contemporary sources indicated that the machine was slower than handwriting, even when used by Burt.

This was because the typographer needed to use a dial rather than keys to select each character.

This lack of efficiency improvement over handwriting ultimately sealed Burt's machine's doom. Both he nor its promoter John D. Sheldon ever found a buyer for the patent.

The modern commercial typewriter would ultimately be invented in 1867 by Christopher Sholes. It began production in 1873. This was typed only in capital letters, but it introduced the QWERTY keyboard.

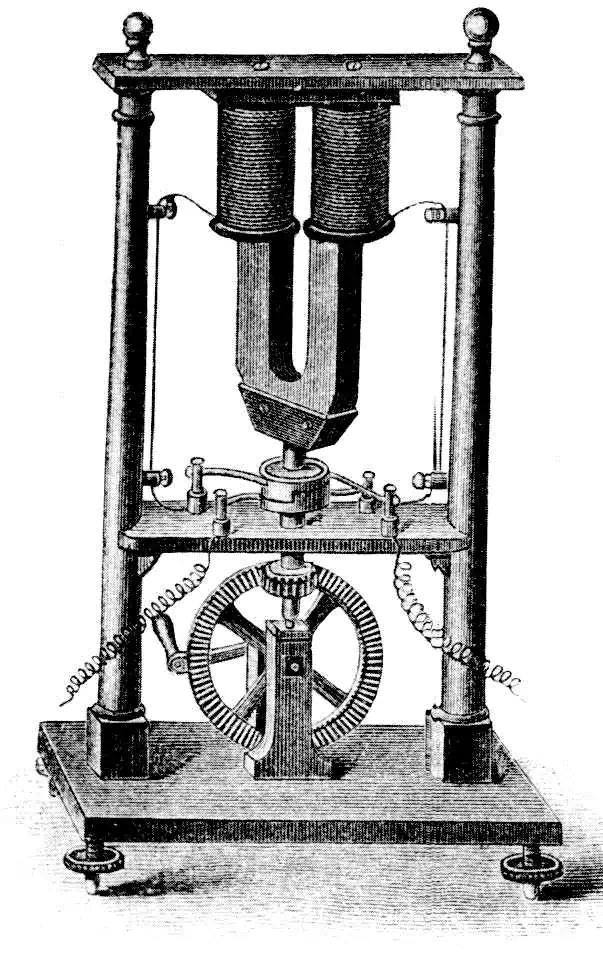

25. The dynamo/electrical generator was another major milestone of the Industrial Revolution

DMahalko/Wikimedia Commons

The dynamo was another great invention of the Industrial Revolution. Michael Faraday discovered the basic principles of electromagnetic generators in the early 1830s.

Faraday noted that the electromotive force is generated when an electrical conductor encircles a varying magnetic flux. This would later become known as Faraday's Law.

Faraday also built the first electromagnetic generator, the Faraday Disk. This was a type of homopolar generator that used a copper disc that rotated between the poles of a horseshoe magnet.

Based on Faraday's principle, the first true dynamo was built in 1832 by Hippolyte Pixii, a French instrument maker. His device used a permanent magnet that was rotated using a crank.

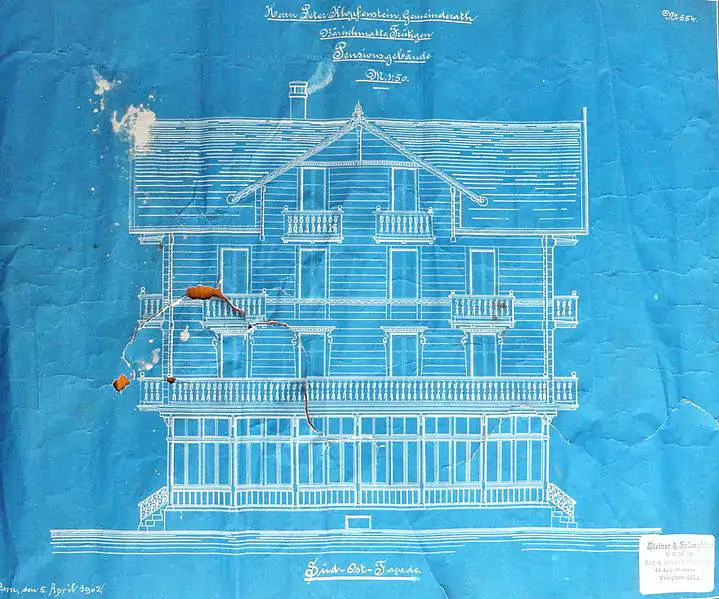

26. Blueprints also came out of the Industrial Revolution

Adrian Michael/Wikimedia Commons

John Herschel, a British scientist and inventor, succeeded in developing the process that was the direct precursor to what we now know as blueprints. Herschel made improvements in photographic processes, particularly in inventing the cyanotype process and variations (such as the chrysotype), the precursors of the modern blueprint process, in around 1839.

This process enabled the production of a photograph on glass, he also experimented with some color reproduction. It is also believed that he coined the term photography.

It wasn't until 1861 that Alphonse Louis Poitevin, A French Chemist, developed 'true' blueprints. He found that Ferro-gallate in gum is light-sensitive. When exposed to light, it turns into an insoluble permanent blue. He successfully postulated that using this coating on paper or other material could be used to copy an image from another translucent document.

Who would have thought this was one of the inventions to come from the Industrial Revolution?

27. The hydrogen fuel cell's potential is yet to be realized

The hydrogen fuel cell was first documented in 1838 in a letter published in the December edition of The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science.

The piece was written by a Welsh physicist and barrister, William Grove. In it, he described his development of a crude fuel cell that combined sheet iron, copper, and porcelain plates and a solution of sulfate of copper and dilute acid.

In the same publication published a year later, a German physicist Christain Freidrich Schonbein also discussed his crude fuel cell that he believed he had invented. His letter described how current was generated using hydrogen and oxygen dissolved in water.

Grove sketched his design later, in 1842, once again, for the same journal. Both of these used similar materials to days phosphoric acid fuel cells.

28. Dynamite was another child of the Industrial Revolution

Cbyd/Wikimedia Commons

Dynamite is yet another invention that can trace its origins to the Industrial Revolution. The Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel first invented this highly-explosive combination of nitroglycerin, sorbents, and stabilizers.

It was one of the world's first safe, manageable explosives. His father's work inspired Nobel as an industrialist, engineer, and inventor who helped build bridges and other structures.

His father, Immanuel Nobel, spent many years trying to find a safer, more effective alternative to black powder but was unsuccessful.

He would later patent it in 1867.

This potent explosive quickly gained wide-scale use worldwide as a far more powerful alternative to black powder. Today, dynamite is mainly used in mining, quarrying, construction, and demolition activities.

29. The internal combustion engine was also born during the revolution

Yet another invention of the Industrial Revolution is the internal combustion engine (ICE). The technology, like many complex pieces of engineering like an ICE, is the product of a long line of scientists and engineers over time.

But, they were first commercialized in the 1860s by Etienne Lenoir. It would take the work of Nicolaus Otto, Gottlieb Daimler, and Wilhelm Maybach to produce the first modern ICE in the 1870s - a working, compressed-charge, four-cycle engine.

George Brayton invented the first liquid-fuel internal combustion engine in the early-1870s. Karl Benz would later produce the first motor vehicles powered by ICEs in the 1880s, and Rudolf Diesel would create his revolutionary diesel engine over a decade later.

30. Another invention of the Industrial Revolution is the humble sewing machine

The sewing machine is also an invention of the Industrial Revolution. In 1755 a German-born engineer called Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal developed an early mechanical device for sewing.

It consisted of a double-pointed needle with an eye at the end. A little later, in the 1790s, an English inventor, Thomas Saint, developed the world's first practical sewing machine, but failed to market his invention with any success.

A little later, in the 1820s, the first practical and commercially produced sewing machine was patented by Barthelemy Thimonnier -- a French tailor. This machine could sew straight seams using a chain stitch similar to that which Saint developed decades ago.

Years later, Isaac Merritt Singer would produce his first straight-stitch sewing machine in 1851, which combined elements of the earlier machines. The company he later founded, Singer, is now widely considered the gold standard in sewing machines today.

31. The incandescent light bulb was also developed during the Industrial Revolution

Yet another invention of the Industrial Revolution that changed the world is the incandescent light bulb. Just like other inventions on this list, like the internal combustion engine, the light bulb is the end product of a long line of inventors throughout history.

One of the lightbulb's significant developments was performed by Sir Humphrey Davy in the early-1800s. He produced the world's first true artificial electric light -- the arc light.

Over the next 70 years or so, the technology would be further refined, with another breakthrough being achieved by Warren de la Rue in the 1840s. He was able to enclose a coil of platinum filament inside a vacuum tube.

It worked, but platinum is far from cheap.

In the 1850s, Joseph Wilson Swan began experimenting with different filament types to act as a cheaper replacement. He eventually perfected his design in the late-1870s. Around the same time, Thomas Edison also began tinkering with his design, which would eventually lead to the founding of the Edison Electric Light Company.

His designs were similar to Swan's, who took Edison to court over copyright infringement. He won and was made a partner in Edison's new company.

32. The modern assembly line was, funnily enough, also a product of the revolution

Siyuwj/Wikimedia Commons

Yet another world-changing invention of the Industrial Revolution was the modern assembly line. This manufacturing process breaks down the assembly process into sections where the final product is sequentially completed along the line.

This helped speed up the manufacturing process considerably and with less manpower than traditionally required. Also termed division of labor, some early forms first appeared in China.

But it would take the Industrial Revolution for the modern assembly line to take form. Great strides were made in the early-1800s by the likes of Marc Isambard Brunel (Isambard Kingdom Brunel's father) and at the Bridgewater Foundry.

Interchangeable parts further pushed the process forward in the early 19th century. Steam-powered conveyor belts were also developed in the latter quarter of the 1800s.

But probably the most significant development was the advent of the moving assembly line. Developed for the Ford Model T and began operation in 1913 at the Highland Park Ford Plant, it continued to evolve after that, using time and motion study.

Today, assembly lines are the core of any factory and are used to assemble anything from automobiles to household consumer goods. Human workers have, for a long time, been progressively replaced with automated machines and robots wherever possible.

33. The tractor revolutionized farming

Tractors, more correctly termed traction engines, were another important invention of the era.

In 1859, British engineer Thomas Aveling converted a Clayton & Shuttleworth portable engine, which had to be pulled by horses from job to job, into a self-propelled one, creating the first real traction engine in the shape we recognize today. To modify, a lengthy drive chain was installed between the crankshaft and the rear axle.

Although there was a lot of experimenting during the first half of the 1860s, by the end of the decade, the conventional shape of the traction engine had developed and altered little over the following sixty years. It was extensively used in agriculture. The early tractors were steam-driven engines for plowing. They were employed in pairs and set on either side of a field to move a plow back and forth between them.

England's hard, damp soil made steam tractors for direct plowing created in Britain by Mann and Garrett less efficient than a team of horses. Where soil conditions allowed, steam tractors were utilized in the United States to direct-haul plows. Agricultural steam engines were still in use well into the 20th century before dependable internal combustion engines were created.

34. The Davy lamp saved thousands of miners' lives

And finally, while a small invention in the grand scheme of things, the Davy safety lamp deserves a place here due to its life-saving purposes.

Sir Humphry Davy created the Davy lamp in 1815 as a safety lamp for use in flammable environments. It consists of a wick lamp with a mesh screen covering the flame.

It was developed for use in coal mines to lessen the risk of explosions caused by methane and other flammable gases, also known as "firedamp" or "minedamp."

The lamp would prove a huge success and be used for many decades before being replaced with more modern electrical lighting.

And that is your lot for today.

The Industrial Revolution was undoubtedly a period of enormous technological advancement and development. It paved the way for many aspects of our modern world and will likely not be matched until significant breakthroughs in our understanding of physics are found.

However, some believe we may be experiencing a new form of industrial revolution right now!

SHOW COMMENT (1)

SHOW COMMENT (1)

A simulated moonwalk in Arizona allowed engineers to test a wearable for future Artemis astronauts.

The engineer who built an airplane in his backyard is flying around Europe with his family

The engineer who built an airplane in his backyard is flying around Europe with his family

Researchers discover people are using the internet for sex

Researchers discover people are using the internet for sexThe great dying: A new study may have revealed the reason behind world's largest mass extinction

A company's nuclear fusion rockets could help us escape the Solar System in our lifetime